Probing the Solar System

___________________________________________________

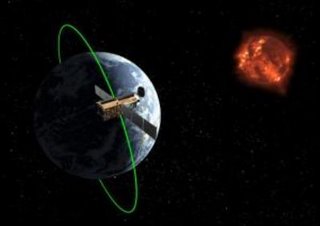

Solar-B's Earth orbit is designed to give it the optimum view of the Sun. Credit JAXA

Probing The Most Energetic Explosions In The Solar System

Solar flares are tremendous explosions on the surface of our Sun, releasing as much energy as a billion megatons of TNT in the form of radiation, high energy particles and magnetic fields. The Sun's magnetic fields are known to be an extremely important factor in producing the energy for flaring and when these magnetic fields lines clash together, dragging hot gas with them, an enormous maelstrom of energy is released.

This boiling cauldron of plasma is ejected at huge speeds into the solar system and high energy particles, such as protons, can arrive at Earth within tens of minutes, to be followed a few days later by Coronal Mass Ejections, huge bubbles of gas threaded with magnetic field lines, which can cause major magnetic disturbances on Earth, sometimes with catastrophic results.

Whilst scientists understand the flaring process very well they cannot predict when one of these enormous explosions will occur. The Solar-B mission, designed and built by teams in the UK, US and Japan, will investigate the so called 'trigger phase' of these events.

"Solar flares are fast and furious -- they can cause communication black-outs at Earth within 30 minutes of a flare erupting on the Sun's surface. It's imperative that we understand what triggers these events with the ultimate aim of being able to predict them with greater accuracy" said Prof. Louise Harra, the UK Solar-B project scientist based at University College London's Mullard Space Science Laboratory [UCL/MSSL].

Solar-B will measure the movement of magnetic fields and how the Sun's atmosphere responds to these movements. Since the Sun is constantly changing on small timescales Solar-B will be able to distinguish between steady movements and the changes that will build-up to a flare.

The spacecraft will be launched on the 22nd September 22:00 UT from the Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency (JAXA) Uchinoura Space Centre at Uchinoura Kagoshima in southern Japan. Solar-B will be launched into a Sun-synchronous orbit allowing uninterrupted viewing.

"The Sun behaves unpredictably and will be as likely to flare during spacecraft 'night' when Solar-B would be behind the Earth, which is why we have chosen a special type of polar orbit that will give us continuous coverage of the Sun for more than 9 months of the year," said Prof. Len Culhane from UCL/MSSL, Principal Investigator of the Extreme Ultraviolet Imaging Spectrometer [EIS] instrument on Solar-B.

Solar-B carries three instruments which have been designed to explore the critical trigger phase of solar flares. The UK (UCL/MSSL) led EIS instrument, an extremely lightweight 3-metre long telescope, will measure the dynamical behaviour of the Sun's atmosphere to a higher accuracy than ever before, allowing measurement of small-scale changes occurring during the critical build-up to a flare.

"In order to make the EIS as light as possible we used the same type of carbon fibre structure, from McClaren Composites, that is used to build racing cars, although being in space will subject the material to many more demands than the average racing car" said Dr Ady James, EIS Instrument Project Manager at UCL/MSSL.

The EIS instrument is complemented by optical and X-ray telescopes and all three instruments will help solve the long-standing controversies on coronal heating and dynamics.

"Solar-B will give us an increased understanding of the mechanisms which give rise to solar magnetic variability and how this variability modulates the total solar output and creates the driving force behind space weather," said Prof. Keith Mason, CEO of the Particle Physics and Astronomy Research Council [PPARC], the funding agency behind UK involvement in the spacecraft. Prof. Mason added, "Predicting the timing and strength of solar flares is critical if we want to mitigate the threat to orbiting spacecraft and Earth-based communication systems".

The Rutherford Appleton Laboratory, part of the Council for the Central Laboratory of the Research Councils [CCLRC], provided the EIS calibration and observing software.

Source: Particle Physics & Astronomy Research Council

_______________________________________________________

Proton Treatment Could Replace X-ray Use In Radiation Therapy

Scientists at MIT, collaborating with an industrial team, are creating a proton-shooting system that could revolutionize radiation therapy for cancer. The goal is to get the system installed at major hospitals to supplement, or even replace, the conventional radiation therapy now based on x-rays.

The fundamental idea is to harness the cell-killing power of protons -- the naked nuclei of hydrogen atoms -- to knock off cancer cells before the cells kill the patient. Worldwide, the use of radiation treatment now depends mostly on beams of x-rays, which do kill cancer cells but can also harm many normal cells that are in the way.

What the researchers envision, and what they're now creating, is a room-size atomic accelerator costing far less than the existing proton-beam accelerators that shoot subatomic particles into tumors, while minimizing damage to surrounding normal tissues. They expect to have their first hospital system up and running in late 2007.

Physicist Timothy Antaya, a technical supervisor in MIT's Plasma Science and Fusion Center, was deeply involved in developing the new system and is now working to make it a reality. He argues it "could change the primary method of radiation treatment" as the new machines are put in place.

The beauty of protons is that they are quite energetic, but their energy can be controlled so they do less collateral damage to normal tissues, compared to powerful x-ray beams. Protons enter the body through skin and tissue, hit the tumor and stop there, minimizing other damage.

Protons are far more massive than the photons in x-rays, and the x-rays tend to pass directly through tissues and can harm living cells along the entire path. The side effects often include skin burns and other forms of tissue damage.

The new machines, in fact, should allow radiation specialists to deposit a far bigger dose of killing power inside the tumor, but spare more of the surrounding normal tissues. This is expected to increase tumor control rates while minimizing side effects.

Because of their high energy and controllability, protons have been used as anti-cancer bullets in the past, with promising results. But medical centers can't easily come up with the $100 million or more needed to build a proton machine dedicated to this medical use. That's because protons are produced inside the huge, expensive atomic accelerators that are usually employed at major atomic research centers, including national laboratories.

Now, Antaya and his colleagues at MIT and at Still River Systems Inc. think they can provide the new machine for far less money, have it occupy just one moderate-size hospital treatment room, and achieve better results than x-ray therapy. MIT is licensing the technology to Still River Systems.

Industry is already showing acute interest in the new technology because more than half of all cancer patients are now treated with radiation, meaning there are two million radiation patients worldwide. That offers a huge market for an effective new radiation system, and the directors of major cancer research and treatment centers are already enthusiastic, Antaya said.

Antaya recalled that the initial push to build a new proton-making system came from a radiation physicist, Kenneth Gall, at the University of Texas at Dallas Medical Center. "He had a good idea for a single-room proton treatment facility, but hadn't found anyone who thought it was possible to build," Antaya said. Gall is now at Still River Systems as a co-founder.

In his own research experience, Antaya had worked with new types of cyclotrons, they were called "atom smashers" years ago, using new "superconducting" coils to generate the necessary magnetic fields. As a result, he could see a "nexus between all the required technologies and how we could pick a reasonable set of properties, with a good chance of being successful," he said.

Building it is quite a challenge, however.

This is an accelerator that's going to be in the room with the patient, so it's quite a difficult design exercise, just in terms of safety issues, Antaya said. But he and his colleagues are betting it will work as expected.

The magnet work of the Technology and Engineering Division of the Plasma Science and Fusion Center, led by senior research engineer Joseph Minervini, is key to the new system. That work has been funded by the U.S. Department of Energy Office of Fusion Energy Science.

Source: MIT 12th September 2006 Science Daily

_______________________________________________________

_______________________________________________________

Famous Quotes

When the rich think about the poor, they have poor ideas. Evita Peron

_______________________________________________________

<< Home